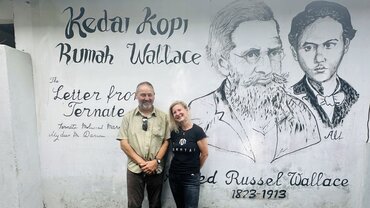

Wallace, Darwin and the letter from Ternate which helped change the world

‘My Dear Mr Darwin’ began the letter Alfred Russel Wallace penned to his fellow naturalist from the Moluccan island of Ternate on 9th March 1858. What followed was an outline of Wallace’s theory of Natural Selection, which would help revolutionise our understanding of the world of nature.

Extracts of Wallace’s ideas were published in a scientific paper in June 1858, jointly with Darwin. The following year, Charles Darwin followed up with his own publication, On The Origin of Species,outlining evolution theory, which shook the world of science and beyond. While Wallace continued to collect beetles, birds and butterflies in the remote islands of the Malay Archipelago, back in London, Darwin stole the limelight. It was not a case of plagiarism - Darwin had himself been pondering on a similar theory since his celebrated around-the-world voyage on The Beagle in the 1830s - but there is little doubt that Wallace has become very much overshadowed by Darwin and his contribution deserves much more recognition today.

Wallace's Journeys to the Amazon and the Malay Archipelago

Alfred Russel Wallace was born in 1823 into an English middle class family in Llanbodic, Monmouthshire, now part of Wales. His family ran into financial difficulties and young Alfred had to leave school aged fourteen, which meant he did not benefit from the academic opportunities his well-to-do contemporary Darwin experienced at Edinburgh and Cambridge Universities. But Alfred also developed a passion for the natural world through his hobby of collecting insects while working as a land surveyor. He was greatly inspired by reading of the voyages of Humboldt and Darwin, so the young self-taught collector jumped at the opportunity to join an expedition himself in 1848 - to South America, where he spent more than four years collecting birds, insects and mammals in the Amazon basin and mapping the Rio Negro tributary. Tragically, he lost nearly his complete collection and field notes when his boat caught fire on the return voyage to England.

Undeterred, Wallace set sail again in 1854, this time to the Malay Archipelago. In the course of eight years, he travelled extensively through the island world of today‘s Indonesia and Malaysia, mostly with his Malay assistant Ali, clocking up 22,000 kilometres and collecting an astonishing 126,000 animal and insect samples, including those of 5000 new species. In his travels from island to island, Wallace noticed a remarkable transition in species when sailing eastwards from Bali and Borneo. On Lombok, Sulawesi and the other eastern islands, the birds and mammals were found to be Australasian in origin, while those to the west seem to originate in continental Asia. The line where this transition is observed is known today as the Wallace Line - at least one legacy of Alfred Russel Wallace’s remarkable discoveries.

Wallace's Theorie on Natural Selection born in Indonesia East of the Wallace Line

It was east of the Wallace Line that the British naturalist took the understanding of the natural world to a new level. Whilst living in a modest house in Ternate and travelling to surrounding islands, Wallace encountered many exotic species from the bird-of-paradise to the golden birdwing butterfly and tree-dwelling marsupials. He started to see a pattern of how the natural world developed and evolved according to the environmental circumstances. During a field trip to Halmahera in early 1858, Wallace suffered from malaria. Resting up in the little village of Dodinga and, as if spurred on by his feverous state, he reported experiencing ‘’a flash of insight’’ about the natural world. After recovering, Wallace returned to Ternate and penned an outline of his theory in his letter to Darwin of March 1858, an extract of which states:

‘’Natural selection is a process by which species adapt over time in response to environmental change and competition. Individuals which happen to have characteristics better suited for the new conditions will be more likely to survive and reproduce, passing their superior traits onto their offspring’’

Wallace's Letter from Ternate

Some weeks later, Wallace’s letter from Ternate caused a huge stir in London. Charles Darwin had been working on what he called his ‘’big book on species’’, which would bring together his own ideas on how natural species evolved - Darwin wanted to get it right - after all he had a reputation in British society to preserve and the subject challenged traditional thinking, especially the creationist position of the Church of England. Darwin revealed his dilemma to his friend, the eminent geologist Charles Lyell, remarking that Wallace’s notes on Natural Selection read like an ‘’abstract’’ of his own planned work. Lyell urged Darwin to publish before ‘’someone else did’’. A scientific paper was rushed to print in August 1858 which, in recognition of Wallace’s letter, was at least published in Darwin and Wallace’s name. Wallace’s permission had not been sought, however, while he continued with his field work on his distant archipelago, unaware of all the furore back in England.

In the years to come, Wallace would be recognised for his contribution to the breakthrough on evolutionary theory, including many scientific awards and the Order of Merit from King Edward VII in 1908. But landmark publications such as Origin of Species and Descent of Man and his high standing in the scientific establishment, meant that Charles Darwin was the much more prominent of the pair. It is even argued that it was the Victorian satirists’ caricatures of the grey-bearded Darwin with the body of an ape, which led to Darwin’s popular fame at the time.

Wallace' Honour in Dodinga on Halmahera Island, SeaTrek and the Wallace Correspondence Project

Wallace was a modest man and took the developments all in his stride. He became a good friend of Darwin, even dedicating to him the journal of his travels through South East Asia, The Malay Archipelago, when it was published in 1869. Back in England, Wallace married at 43, fathered three children and became a prolific writer of books and papers, straying into all kinds of topics of the day, from social reform to spiritualism and whether Mars could sustain life. He struggled financially at times, never experiencing the kind of fame and fortune of his more illustrious colleague. After Wallace’s death in 1913, his name and reputation slipped into obscurity, and even in Britain he became little known outside of academic circles. Fortunately, that is changing and a number of projects, from publications to statues and TV documentaries have raised public awareness of the great naturalist and explorer, notably the tireless work of the Wallace Correspondence Project, led by Dr. George Beccaloni

Today, thanks to the support of our valued partner Sea Trek, the East of Wallace team witnessed a very special occasion in the sleepy Halmaheran village of Dodinga. We had the privilege of joining George Beccaloni and William Russel Wallace, great grandson of Alfred, for the unveiling of a commemorative stone and plaque, performed together with the Governer of North Molluca and the British Ambassador to Indonesia, under the gaze of the charming villagers of Dodinga. The plaque commemorates the unlikely place where Wallace, in his malarial fever, devised his theory of Natural Selection. It is one more step to rediscovering one of the world’s greatest scientists - and how appropriate to find it here, where Alfred Russel Wallace seemed most at home, amongst the exotic birds and butterflies of this magical island world, east of the Wallace Line.

Alan Cunningham, 5th October 2024

Onboard the Ombak Putih, sailing along the west coast of Halmahera

Would you like to follow on Wallace's footsteps?